Is it worth implementing High Potential programs in organizations? And what mistakes should be avoided?

How to retain valuable employees?

Who is a TALENT?

Before we move on to specific examples, it is worth defining who is a talent. The shortest definition I have encountered describes talent as „a person who stands out from the crowd.” However, it is worth specifying this definition, especially when communicating with individuals involved in the decision-making process regarding talent selection and considering the various selection criteria.

For the needs of one organization where I was implementing the „Talent Academy,” we jointly agreed that a talented person is both effective over a long period of time and has high potential. What does this mean in practice? Effectiveness, meaning sustainable business results, can be relatively easily measured by comparing, for example, the results of the last two annual evaluations or analyzing the success of implemented projects. However, how to assess potential and what is it?

The most accurate and realistic definition we found for potential was using the term „Learning Agility.”

To help the managerial staff involved in the project identify high-potential individuals in their teams, we specified that these are employees who, according to the definition of „Learning Agility,” demonstrate the ability and willingness to learn from experiences and apply the acquired knowledge effectively in new conditions. The supervisor of the potential talent would answer questions related to each of the five components of „Learning Agility”:

Mental Agility – the ability to work with concepts and ideas

Is your employee curious? Do they try to get to the heart of the matter and understand the causes of the situation? Do they feel comfortable in a complex and changing environment? Do they constructively question the status quo? Do they try to find solutions for difficult and complex issues?

People Agility – the ability to build relationships and collaborate with people

Does this team member communicate easily with colleagues? Do they easily take on different roles in the team? Do they have an open mind? Can they handle conflicts constructively? Do they understand others? Do they strive to help others develop? Do they accept diversity?

Change Agility – acceptance of undefined situations and the ability to lead changes

Does the candidate for talent seek and introduce new solutions? Do they test new proposals? Can they handle skepticism and resistance to change? Do they easily accept unidentified situations?

Results Agility – the ability to seek solutions and achieve results despite adversity

Does your employee’s charisma, attitude, and way of working increase the efficiency of others? Do they easily adapt to new challenges? Do they gather high-potential individuals around them, questioning standard methods of operation?

Self-awareness – self-awareness

Does the person you consider a talent assess themselves correctly? Do they see their strengths and weaknesses? Do they have self-awareness of their limitations as well as their strengths? Do they have humility?

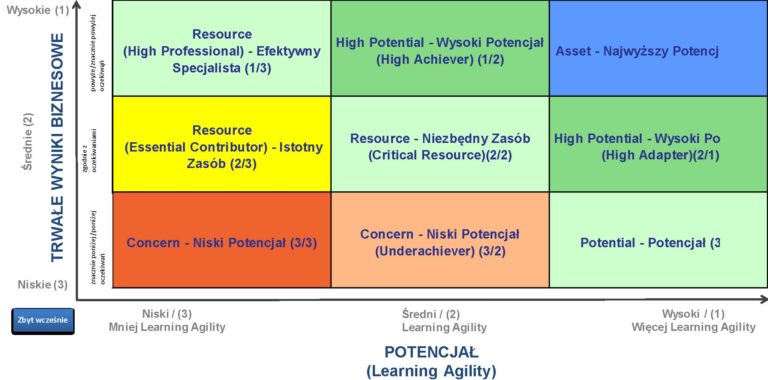

After answering the above questions and checking the business results/effectiveness from the last two years, the individual could be placed in one of nine categories/fields in the matrix created by combining these two dimensions.

Ultimately, the Talent Program included individuals from the „High Achiever,” „Asset,” and „High Adapter” categories.

How can we objectively identify and select talents in the organization? How can we properly "calibrate" this process?

In the following part of the article, I answer these questions.

Sponsorship of top management

Responsibility for development on the Talent's side

Project management

Taking care of building a community

How to ensure objectivity and transparency in the Talent selection process?

From my perspective, it is worth first defining a specific target group (for example, experts and mid-level managers from a specific level within the organization) to address the program and invite everyone to participate through open communication. I am not in favor of keeping talent programs confidential. Therefore, in my opinion, it should not be a „top-secret” process of pointing out specific individuals. In such situations, there may be suspicions of favoritism by the Board and senior management towards selected individuals. That is why, in my opinion, everyone in the chosen target group can apply for the talent program.

On the other hand, based on my experience and statistical data, talented individuals typically make up about 5-7% of a given population. Additionally, talent programs should be perceived as exceptional and elite. It is also important to be aware that conducting such a multi-month development program is not cheap and consumes a significant budget. Therefore, to narrow down the number of people at the very beginning, it is worth using selection criteria that will be openly communicated to the target group from the start.

These could include, for example, a certain length of service, a specific SOOP score in the last two years, a declaration of mobility and willingness to participate in international exchange programs, knowledge of English at a certain level, etc.

It is also important that the individual applying for the talent program puts some effort into completing an application in which they describe their motivation for participating in the program. This topic should also be explored during direct interviews with talent candidates.

In one organization where I implemented such a program, each HRBP conducting the interview had a prepared set of questions (a structured interview) to best compare candidates (similar to internal recruitment processes).

From experience, I know that the most important thing is to use specific and transparent tools provided by an external company – the same for everyone. For example, appropriately selected skills tests tailored to the industry can be used. I used a set of SHL tests (verbal, numerical, and inductive) as one of the key elements of talent recruitment.

However, the most objective and transparent tool for identifying a talent group, in my opinion, is the Development Center. It should be conducted by external assessors.

What are the advantages of DC? First of all, the participation of an external company and assessors involved in observing exercises performed by the talents ensures the objectivity of the evaluation. We can also ensure the transparency of criteria through standardization based on selected key competencies (usually chosen from the competency model existing in the organization). In practice, a set of exercises is proposed, and each competency is observed during at least two exercises. Each participant is observed by at least two assessors, and then their evaluations are compared and discussed.

If the group of talent candidates includes both experts and managers, separate sessions should be conducted for these two groups, assessing slightly different competencies. Each DC participant receives an individual report after the session, with descriptions and developmental recommendations. Additionally, there is coaching feedback, where the candidate also receives development recommendations and finds out if they were accepted into the talent group.

We're starting the program

When our talents are selected, they begin their several-month-long development program. What should we pay attention to when creating such a program?

It is definitely worth considering how adults learn – in accordance with the 70/20/10 rule. Research shows that 70% of our skills are acquired through practice and our own experiences, i.e., actions taken during work on a given task or leading a project. Therefore, it is essential to plan an element of self-work in the talent development program – preferably in a project group, where a new idea to improve business operations is created and developed from scratch. Thanks to this approach, we will also see a return on our investment in the talent program in the form of a new product/service or a process that improves customer service. Personally, I was truly impressed with the innovation and creativity demonstrated by talents in the projects I implemented.

The second important element of adult learning (20%) is observing others and learning from them. Mentoring programs work exceptionally well here. Of course, the organization and the mentors themselves need to be adequately prepared for this. A group of mentors – individuals who volunteer for this role – must be trained, and then the talents should be given the opportunity to choose their mentor. A good practice during the mentoring process, which usually lasts several months (from 5 to 9 sessions), is also so-called three-way meetings involving the mentor, mentee, and HR representative. Tools that assess natural communication styles (e.g., Extended DISC) or thinking and action styles (FRIS) can also be helpful. Individual work with such reports, plus a meeting with a certified advisor in the given tool, can provide the talent with valuable feedback in the development process. These types of tools have also worked excellently for me in project groups (during team coaching sessions). This way, team members more easily chose their natural roles within the team, being more aware of their potential (e.g., project leader, analyst, executor, etc.).

Of course, we should not forget about traditional training, language courses, webinars, e-learning, or simply a good book that the mentor recommends to the talent. Although this constitutes only 10% of adult learning, it is still an aspect worth remembering when designing a development project for talents.

At the end of the project, it is worth evaluating it and also accounting for the tasks completed by the participants. In most projects, these elements included:

– The mentor prepares a final development report after the process and discusses it at the three-way meeting,

– Talents from the various project groups present the implementation effects of their ideas to the Board,

– Re-conducting the Development Center (DC) and measuring the increase in competencies.

I strongly encourage you to thoughtfully implement talent programs in your organizations. If you would like to learn more about specific „case studies” and tailored solutions from the financial, insurance, or logistics sectors, I invite you to the training sessions I conduct, both in open forms and designed for specific organizations.

The author of the article is Beata Molska – business psychologist, long-time HR Director, Managing Director of HR Accelerate, business trainer, coach, MBA graduate from the Leon Koźmiński Academy, Interim HR Manager.